More than 92 million Americans live with one or more cardiovascular disease –that’s one in every three (Benjamin et al., 2017). As a health and exercise professional, you will at some point encounter someone managing a cardiovascular disease. It is important to have a general understanding of common types of cardiovascular diseases, their symptoms, and best practices for exercise program design in disease management.

Hypertension

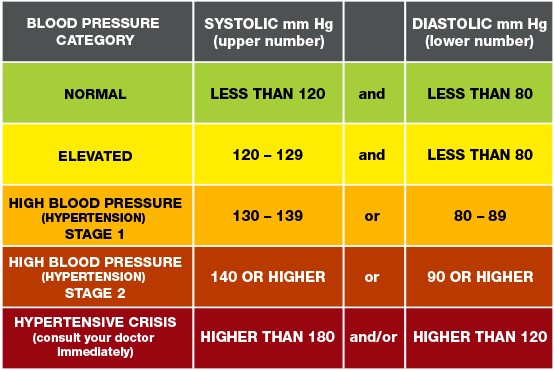

Blood pressure is a measure of the force of your blood against the walls of your blood vessels as your heart pumps. Systolic blood pressure (top number) is the pressure your blood is exerting against your artery walls during the heart’s contraction or beating phase. Diastolic blood pressure (bottom number) is the pressure your blood is exerting against your artery walls while the heart is relaxed. Optimal blood pressure is less than 120/80. The American Heart Association recognizes the five following blood pressure categories:

- Normal

- Elevated

- Hypertension Stage 1

- Hypertension Stage 2

- Hypertensive crisis

Nearly 78 million Americans have high blood pressure, but about 30 percent of adults with high blood pressure are not even aware they have it. This is because hypertension often has no external symptoms.

Exercise can benefit people with high blood pressure by reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke. Additionally, people being treated for hypertension who adopt and adhere to a regular exercise program are often able to reduce the amount of medication they have to take over time. While exercise is a key player in the management of hypertension, health and exercise professionals should be aware of a few important exercise precautions:

- Some blood pressure medications such beta-blockers can affect heart rate, so heart rate monitors may not be accurate indicators of exercise intensity. Teach participants how to use Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) or the Talk Test to monitor exercise intensity.

- When possible, blood pressure should be measured before exercise. Exercise should be avoided if the systolic number is greater than 200 and/or if the diastolic number is greater than 115. Readings this high also warrant a call to the physician to see if medication may need to be modified.

- Hydration is important for all exercisers, but this is especially true for those being treated for high blood pressure. Medications such as diuretics can affect hydration levels and the body’s ability to regulate temperature.

Peripheral Artery Disease

Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) is a leading cause of disability in people over 50. PAD occurs when atherosclerosis (plaque build-up) develops in the extremities such as the arms, feet, calves, or legs. Smokers and people who have diabetes, have hypertension, and those with high cholesterol are at an increased risk. Up to 40% of people with PAD experience intermittent claudication—pain or cramping in the legs or feet with walking or exercising (Sorace et al., 2010). Because people with PAD are at an increased risk for heart attack, stroke and other serious complications, health and exercise professionals should only design exercise programs for clients who have been cleared by their physician to exercise. Furthermore, the following precautions should be applied to program design:

- Exercise tolerance and pain management should be prioritized. Exercising through pain could exacerbate PAD discomfort, so participants should be encouraged to monitor pain during exercise. Intensity should be adjusted as needed.

- Walking should be prioritized over other forms of exercise. Walking has been shown to both reduce claudication and improve ambulatory function in people with PAD (AHA/ACC, 2017).

- Resistance training exercises should be incorporated into the exercise program progressively and should emphasize the muscles of the hips, thighs, and lower legs.

Exercise after Heart Attack

Each year, more than 700,000 Americans experience a heart attack. Roughly one-third of these heart attacks happen in people who’ve had a previous heart attack (CDC, 2018). Exercising after a heart attack can be scary, but most physicians advise a physical activity program to reduce the likelihood of patients developing additional heart problems. Patients who participate in clinical cardiac rehabilitation programs have safer and faster recovery rates. Furthermore, new research from the SWEDEHEART registry study found that increased physical activity levels in the first year after heart attack were associated with lower mortality rates in the immediate years following the heart attack (Ekblom et al., 2019). After being released from clinical cardiac rehabilitation programs, many patients will be advised to continue their exercise program with the support of certified health and exercise professionals in settings such as health clubs and fitness centers. Personal trainers and group fitness instructors should encourage participants to follow physician directives and should be aware of the following post-heart attack exercise recommendations:

- Start off slowly with an aerobic activity such as walking. Increase the intensity and duration of the exercise program over time.

- Weight lifting can have an acute and dramatic effect on blood pressure. For this reason, resistance training programs should be discussed with the primary care physician prior to being incorporated into the exercise program. Resistance exercises that involve isometric contractions should be avoided (e.g. holding a plank).

- Excess heat can put a strain on the heart, so hot yoga and other heat-based exercise programs should be avoided.

- Working through the emotional and psychological trauma of recovering from a heart attack can affect mood and energy levels, especially in the first two to six months. Encourage participants to have a “day-by-day” attitude with their exercise expectations.

Interested in learning more about working with clients managing medical conditions? Check out NETA’s Physical Activity for Special Medical Conditions home-study course.

References:

- American College of Cardiology (2017). New ACC/AHA High Blood Pressure Guidelines Lower Definition of Hypertension.

- Benjamin, E., Mozaffarian, D., Go, A., Arnett, K., Blaha, M., Cushman, M. & Turner, M. (2017). Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics –2017 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 135,10.

- Centers for Disease Control (2018). Heart Disease Facts.

- Ekblom, O., Ek, A., Cider, A., Hambraeus, K., & Borjesson, M. (2019). Increased Physical Activity Post Myocardial Infarction Is Related to Reduced Mortality: Results from the SWEDEHEART Registry. Journal of the American Heart Association, 7, 24.

- Gerhard-Herman, M., et al. (2017). ACC/AHA 2016 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 69, 11.

- Sorace, P., Ronal, P. & Churilla, J.R. (2010) Peripheral Arterial Disease: Exercise is Medicine. ACSM’s Health and Fitness Journal, 14,1.

- Gerhard-Herman, M., et al. (2017). ACC/AHA 2016 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 69, 11.

Contributed By:

Jennifer Turpin Stanfield, M.A. (Exercise Science), is the Assistant Director for Fitness and Wellness at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, a fitness writer, and a national presenter for NETA. She has more than 15 years of experience in the health and fitness industry and is passionate about helping others live healthier lives through the adoption and maintenance of positive health behaviors.

Jennifer Turpin Stanfield, M.A. (Exercise Science), is the Assistant Director for Fitness and Wellness at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, a fitness writer, and a national presenter for NETA. She has more than 15 years of experience in the health and fitness industry and is passionate about helping others live healthier lives through the adoption and maintenance of positive health behaviors.